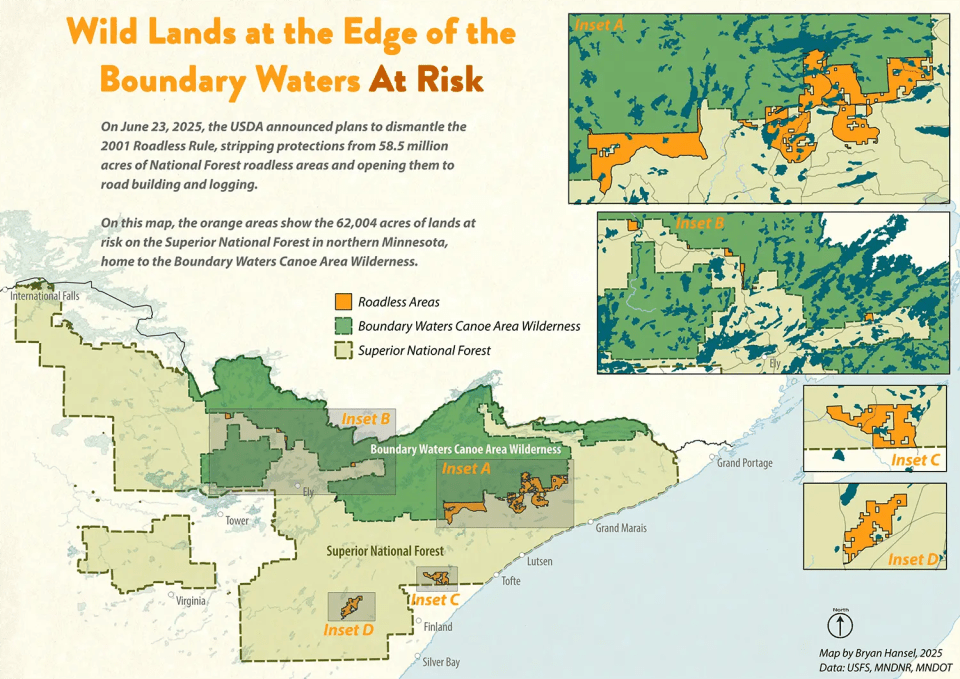

This summer, my 10yo took a wilderness skills class offered by the Friends of the Boundary Waters and run locally in Grand Marais by Sarah Bransford, Friends’ Northern Education and Outreach Coordinator. At the beginning and end of the course, Bransford had the kids complete an exercise designed to help the students and the instructor identify how skilled students were in important outdoor wilderness skills. This exercise could be completed by anyone who enjoys spending time outdoors.

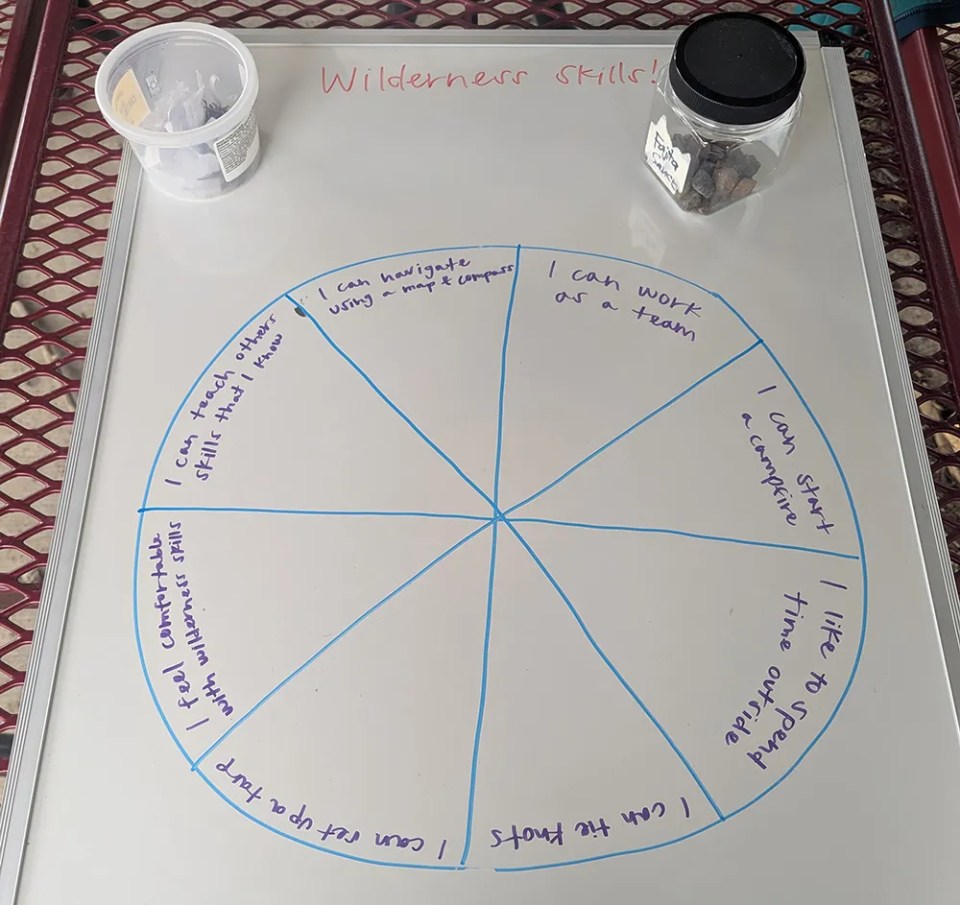

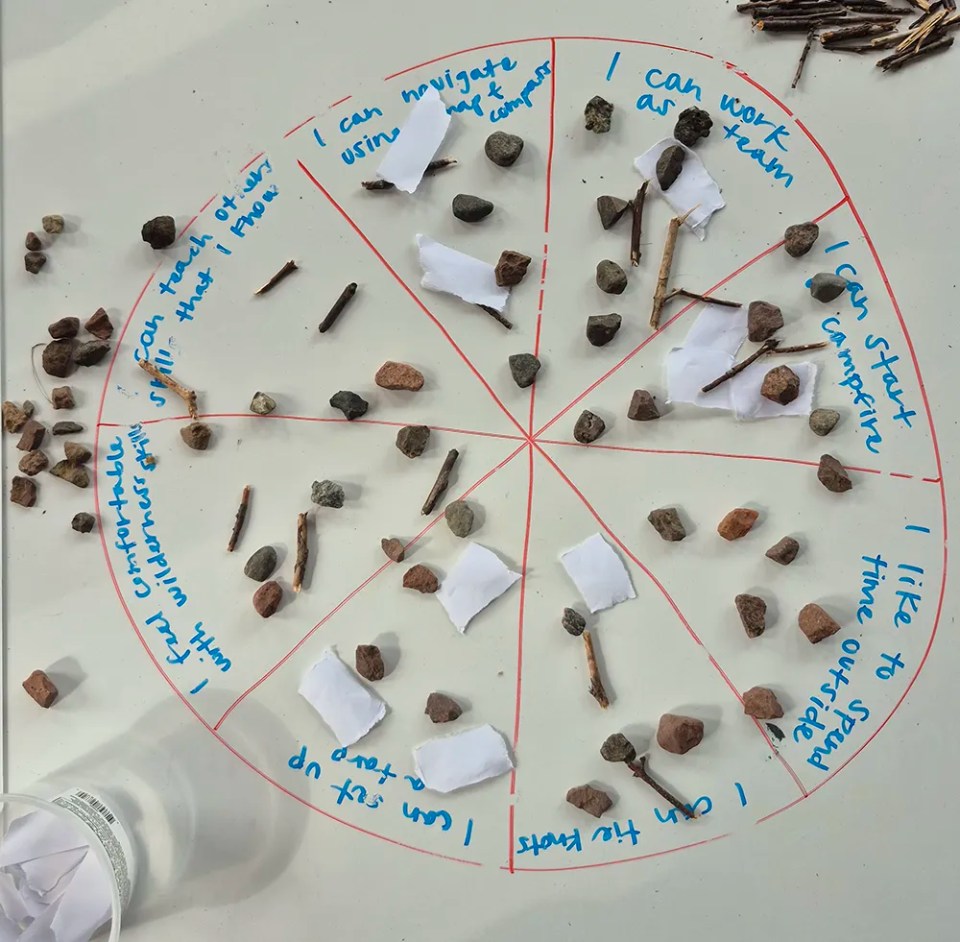

The exercise used a pie chart representing different wilderness skills, including:

We may earn commissions if you shop through the links below.

- I feel comfortable with wilderness skills.

- I can teach others skills that I know.

- I can navigate using a map and compass.

- I can work as a team.

- I can start a campfire.

- I like to spend time outdoors.

- I can tie knots.

- I can set up a tarp.

At the start of the summer, kids ranked each skill using paper, twigs, or rocks: paper meant paper-thin knowledge, a twig meant room to grow, and a rock meant rock-solid knowledge.

During the summer, the class covered each of these skills as a topic for the kids to learn. Bransford chose a mix of skills useful for a wilderness trip that balanced life skills, such as teamwork and teaching; practical skills, such as starting a fire and setting up a tarp; and skills to help students feel comfortable outdoors. Even though every skill in the mix is important, the mix allowed each student a different path towards gaining knowledge that could align more with their personalities.

Bransford said, “There are so many ways to assess student learning and growth in the classroom — tests, surveys, quizzes, etc.. In environmental education, we have the opportunity to use the outdoors as our classroom and we often get to do things outside of the box. This assessment allows us to physically see the changes from the start of a program to the end.”

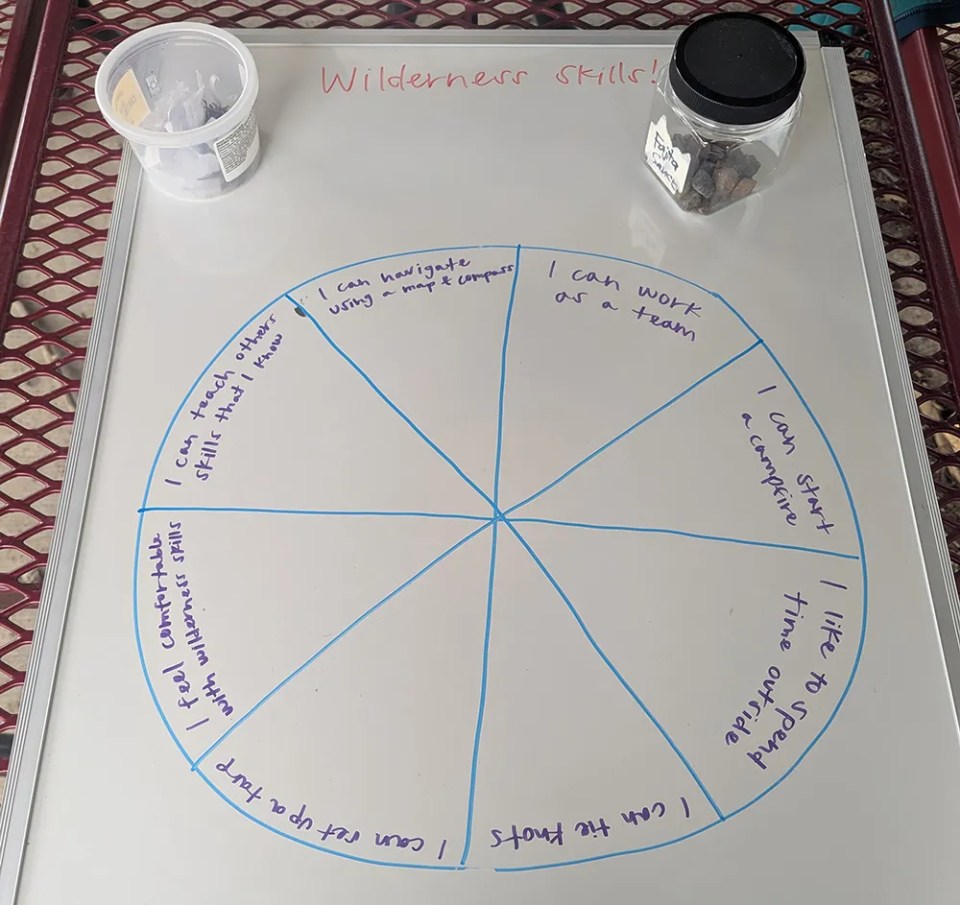

To measure improvement, Bransford ran the exercise again on the last day, after teaching the final skill, fire-making, a skill the students had eagerly anticipated. After the kids placed paper, a twig, or a rock on each piece of the pie, the overall improvement of the group could be seen by comparing the new placements to a photo taken at the beginning of the course.

My 10yo said about the exercise, “It helped you see how you improved and how much you learned based on your choices before and after.”

This exercise gave students a tangible way to see their growth and reinforced the importance of setting goals while teaching the value of reflecting on progress. By the end of the course, each student could recognize the skills they had gained, the confidence they had built in the outdoors, and how teamwork made learning wilderness skills easier. In structuring the course this way, Bransford demonstrated that wilderness skills and travel are just as much about personal growth as they are about practical abilities.

About the students’ growth, Bransford said, “It was awesome to see the growth in skills firsthand through the lessons, but also through the change in objects they chose to place for the statements on either end of the program.”